EEG/QEEG Assessment

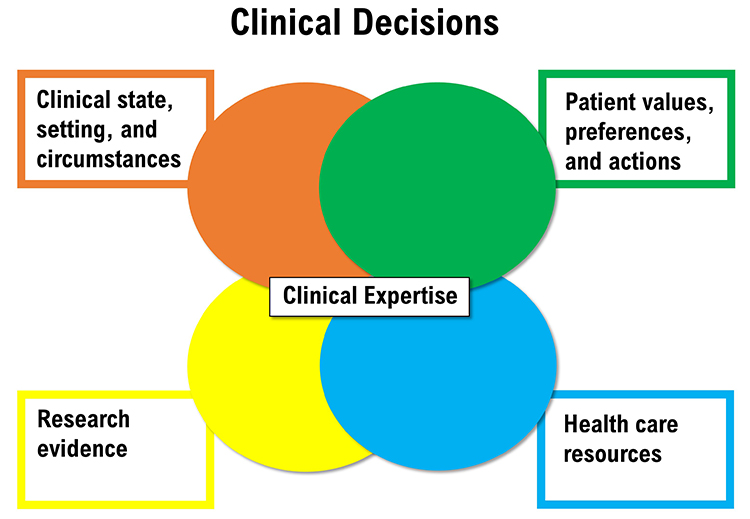

Intake assessment is the foundation for diagnosing and selecting evidence-based interventions to treat symptoms or improve performance. Assessment should be multimethod, evidence-based, and culturally competent.

Multimethod assessment means using several assessment tools since no single tool can evaluate all relevant personality and behavioral domains. Depending on provider scope of practice and client presenting concerns, an intake may include a questionnaire, interview, objective personality tests, inventories, and behavioral assessment (Pomeranz, 2020).

Evidence-based assessment reflects the movement toward evidence-based treatments. Professionals should select measures that work and are psychometrically validated (e.g., reliability, validity, and clinical value). For example, the Beck Depression Inventory-II is widely used to help diagnose adult depression (Pomeranz, 2020).

Culturally competent assessment is sensitive to a culture's definition of normality and abnormality. Providers understand the relevant cultural norms of the populations they serve (Pomeranz, 2020). They avoid overpathologizing and labeling culturally normal behavior as abnormal, by viewing behaviors, cognitions, and feelings using the lens of the client's culture [rather than the provider's culture]. Dana (2005) has described ignorance or insensitivity to cultural norms as cultural malpractice.

Intake assessment has several purposes and methods. The use of these methods produces various quantitative and qualitative types of information. After collecting intake information, the practitioner integrates it with EEG findings and their clinical experience and knowledge of the science on which neurofeedback is based. The practitioner then shares a holistic summary with the client to arrive at a mutually agreed-upon common understanding of the presenting problem, a goal, and treatment options to decide whether to embark on a particular course of NFB training. Graphic © Motortion Films/Shutterstock.com.

BCIA Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses IV. EEG/QEEG Assessment and covers Baseline Assessment, EEG/QEEG Assessment, Ongoing Assessment, and Assessment Demonstration.

A. BASELINE ASSESSMENT

This section covers Intake Assessment, EEG Assessment for Neurofeedback, and Integration of Intake and EEG Assessments.

Intake Assessment

Purposes of Intake Assessment

The general purposes of intake assessment include gathering information, sharing information, and decision-making. In parallel to these, an essential purpose is to build a trusting working relationship that inspires confidence that neurofeedback will help. The results of the intake assessment describe the problem qualitatively and quantitatively and provide the baseline against which progress is measured. The information from intake contributes to constructing a formulation of the problem, that is, understanding why the problem occurs and what will alleviate it. This formulation sets the stage for planning neurofeedback training and helps the client give informed consent. In some clinical practice situations, another purpose may be to diagnose.Optimum Performance Assessment

Some practitioners focus their neurofeedback practice and biofeedback on what is variously known as peak performance, optimum performance, or simply performance training. Individuals who present for such training do not generally perceive themselves as having a "presenting problem" but primarily want to improve their performance in a sport, a musical career, academic achievement, or other endeavors. For such clients, assessment goals are quite similar to that of the clinical client. Identifying levels of function and differences from typical and other measures can be beneficial in guiding optimum performance training. The ultimate goal is performance enhancement. The desired outcomes are often measured by indicators specific to the client’s interests, such as improved scores, better ratings, improved musical opportunities, improved academic results, and the like.When working with optimum performance clients, the assessment may reveal a clinical issue, and sharing this information with the client can be a delicate task. Also, practitioners who are not licensed or registered health professionals may not even recognize such issues and may train the client in ways that may exacerbate such findings. Thus, it is vital for practitioners working with optimum performance clients to use comprehensive assessment techniques described in this section to ensure a thorough understanding of the client is obtained to avoid adverse outcomes.

Intake Assessment Methods

A neurofeedback practitioner's methods during their intake assessment are guided by the nature of the presenting problem, goal, practitioner skill set, and client's wishes. Some of the methods outlined below (e.g., questionnaires and rating scales) may be carried out before first meeting the client, whereas others (e.g., tests) may occur during or after an initial appointment.Preliminary Steps

After the client or referral source contacts the practitioner to request neurofeedback, the practitioner may use that initial contact to collect basic background information, either by phone or by sending a questionnaire. Suppose a background questionnaire is sent to the client. In that case, it may be accompanied by standardized or non-standardized rating scales or other questionnaires that the client is instructed to complete and bring with them to their first face-to-face meeting. Alternatively, background forms, questionnaires, and rating scales may be administered at the practitioner’s office before the intake interview. Some questionnaires and tests may even be completed online prior to the first face-to-face meeting. If the client is a child, then questionnaires and rating scales may be sent to the parent or some other significant person in the client’s life, such as a teacher. Consent forms can also be sent in advance.Introduction and Consent

For the first face-to-face meeting, the provider needs to introduce themself and outline the methods involved in the intake assessment. This enables the client to participate to the best of their ability. An essential part of intake assessment occurs at the outset with a review of confidentiality and the limits of confidentiality before verifying that the client then wants to proceed. Consent should be documented.Throughout the intake assessment, the provider should use active listening skills and other supportive communication skills to build a working relationship with the client (Silverman et al., 2013). The use of these skills fosters trust and credibility and puts the client at ease to provide the best possible information to the practitioner.

If identifying information details are not fully collected before the intake interview, the practitioner can ask the client directly for particulars such as name, birthdate, address, phone number, and information related to billing and whom to contact in the case of an emergency.

Problem Description

Following this opening introduction, information needs to be gathered about the client’s presenting problem and goal (Schwartz, 2016). This may begin with a simple open-ended question, allowing the client time to respond. A great deal can be learned in these first few minutes of an interview by listening to clients present their concerns and goals unimpeded and in their own words. The practitioner can then better follow up with specific questions to understand the problem more thoroughly.Inquiry about the details of the presenting problem helps to construct a description or definition of the client’s primary concern. The problem may be an excess or a deficit and may relate mainly to the client’s emotional, thinking, or somatic functioning. The problem definition may include information related to frequency, intensity, and duration of occasions when the problem occurs.

Context matters so that motivational conditions, antecedents, and consequences of the behavior may be helpful to describe. When the problem first had its onset and surrounding circumstances may be relevant to the assessment. How the symptom has waxed and waned over time and factors that worsen or relieve it can be valuable pieces of information. What the client and others have attempted insofar as changing the problem is also essential, and whether the client is receiving any ongoing treatment. How the issue affects or limits the client helps to illustrate the severity of the concern.

The provider and client use this information to define a goal for training, for example, to decrease a problem that represents an excess of some sort or to increase function that is deficient in some respect. Of course, the results of EEG assessment are part of goal-setting.

Personal and Family History

Information about the larger context of the problem is essential (Stucky & Bush, 2017). Categories of such information are referred to as personal and family history. The client’s personal history includes medication, drug and alcohol use, diet and exercise, sleep, medical issues, psychiatric problems, family and social relationships, education, work experiences, legal matters, and military service. In several of these categories, it is helpful to inquire about treatment, training, and unique accommodations that the client may have had. The client’s typical level of function is beneficial to elicit. This may be done for personal care, completion of domestic chores, socialization, community access, education or work, and leisure and recreation.Family history contains relevant information about parents, siblings, and possibly other family members. Although topics noted for personal history can serve as areas of inquiry about family members, it is usually the case that collection of family history information is more focused and limited to items that are particularly relevant to the client’s presenting problem and goals (e.g., medical and psychiatric concerns).

Diagnostic Interviewing

For some registered/licensed health professionals, the intake information may contribute to making a diagnosis. Several semi-structured interview formats have been developed to elicit information for making a psychiatric differential diagnosis. Medical practitioners may also make a diagnosis based on an interview, physical examination, and test findings.Barriers, Strengths, and Client Perspective

In addition to describing the problem and its course and outlining likely contributing factors, the intake interview also examines possible personal, social, and material resources available to aid in problem resolution. These may include, for example, motivation, encouraging family members, and access to transportation or the internet. Barriers may similarly be personal, social, or material. Additionally, the client’s view of the causes of the problem and what it will take to remedy it are valuable points of inquiry.Behavioral Observation and Mental Status Examination

The client’s way of moving and speaking during the intake interview can be very informative in arriving at a description of the problem and goal and understanding the client.In some clinical situations, the practitioners may administer more formal questions to understand the client’s emotional and cognitive condition. A mental status exam (Sadock et al., 2017) provides a format for observation and briefly assessing mental functioning. Topics include speech, emotion and affect, thought content and form, perceptual disturbances, cognition, reasoning, insight, and judgment.

Collateral Interview

Especially with clients who may be unable to provide reliable information, an interview with a close relative or someone with significant direct experience with the client is beneficial. This information may fill in gaps left from the client interview and add new information. Inconsistencies between the client and collateral information may also suggest potential client deficits.Reports

Several types of reports may be relevant to intake assessment. These include medical and psychiatric reports and academic and vocational information. If the client has been referred by another professional, a report from that professional can be illuminating. Although such a report may be written, a phone conversation with a referral source can be very informative. Such a conversation can help to clarify the reason for referral, attainable goals, and likely predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating causes for the problem. The client should be asked for their consent to request reports that are likely to be helpful.Questionnaires and Rating Scales

Questionnaires often consist of checklists and places for clients to respond in their own words. This allows the client to provide basic background information, problem description, and personal history. Items may be open-ended and qualitative (e.g., describe your concern), closed-ended (e.g., have you ever had a seizure), or multiple-choice (e.g., check each type of caffeinated beverage you drink).Rating scales help to quantify a problem (Baer & Blais, 2010). They may be standardized and have norms that compare the client’s results with those of groups matched to the client, for example, based on age or education. Alternatively, they may be constructed with items the provider has developed for use in their specific setting and may or may not have norms developed in the practitioner’s office.

Both questionnaires and rating scales can collect information about cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physical symptoms or problems (Psychology Tools, n.d.). They can also gather information about the functional consequences of symptoms: the effect that they have on practical, real-world ability and social adjustment (Űstűn et al., 2010).

Information from questionnaires helps describe the presenting problem in qualitative terms and gives the provider insight into how the client sees the problem. Rating scales, together with EEG results, provide quantification of the problem and serve as a baseline for recognizing progress or the lack of progress once training has begun.

As noted above, questionnaires and rating scales can be sent to the client in advance of the intake interview or completed immediately before or after the interview. Collecting information by questionnaire can make the intake interview much more efficient and help focus the interview on the most salient aspects of the client’s concerns.

Whereas some questionnaires and rating scales are proprietary, others are available in the public domain. Informant versions of some questionnaires are also available.

Cognitive Tests

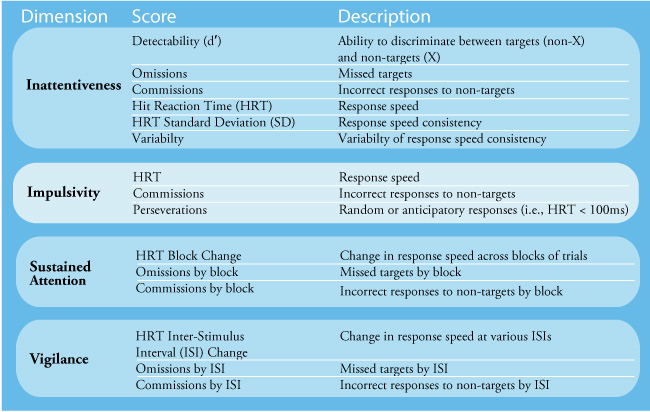

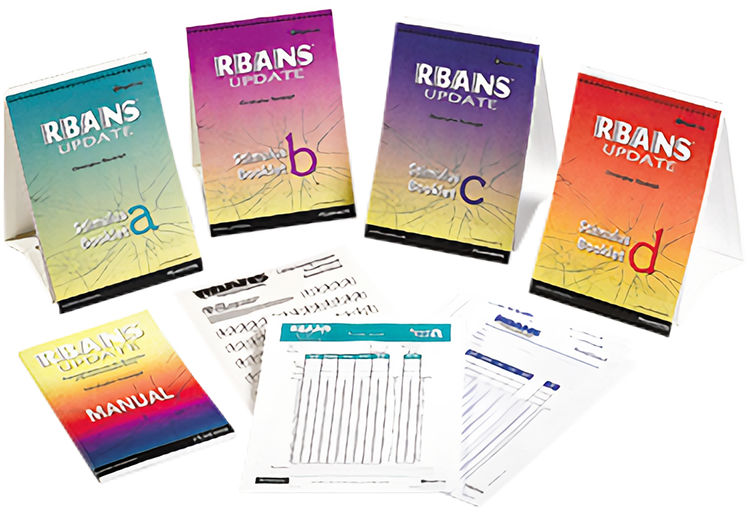

Not only in research settings but frequently in clinics, practitioners will often administer tests of thinking and cognition (Lezak et al., 2012). Depending on the goals of neurofeedback for a particular client, domains assessed may include one or more of the following: attention, memory, language, visual-spatial perception and construction, and executive functioning. Intellectual functioning, academic performance, sensorimotor ability, and effort/performance validity may also be assessed. For example, deficient attention may be why the client requested neurofeedback. A continuous performance test such as the Conners Continuous Performance Test (2014) may be used to assess sustained attention and distractibility. Graphic © Pearson.

Or, improved academic performance may be the client’s goal, with the practitioner using an educational screening instrument such as the Wide Range Achievement Test (Wilkinson & Robertson, 2017). Graphic © Pearson.

Alternatively, a measure of intelligence (e.g., Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV; Wechsler, 2008) or collection of executive function or cognitive self-regulation measures may be of interest (e.g., Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System; Delis et al., 2001). Cognitive test batteries have several tests that assess representative domains of cognition and may include, for example, measures of aspects of attention, memory, and executive function (e.g., CNS Vital Signs; Gaultieri & Johnson, 2006). Graphic © Pearson.

Tests should be selected critically, considering standardization methods, normative groups, reliability, and validity. Many tests are available only to professionally qualified health practitioners, while many other tests can be purchased with fewer requirements. While many tests use paper and pencil or objects to manipulate, additional tests are administered by computer.

Those tests that use paper and pencil, or manipulable objects, usually require administration by a well-trained individual. However, those tests administered by computer reduce the cost of clinician time, both for administration and scoring. Nevertheless, a practitioner should interpret results with appropriate professional background for the results to have validity and value for the client.

Psychophysiological Assessment

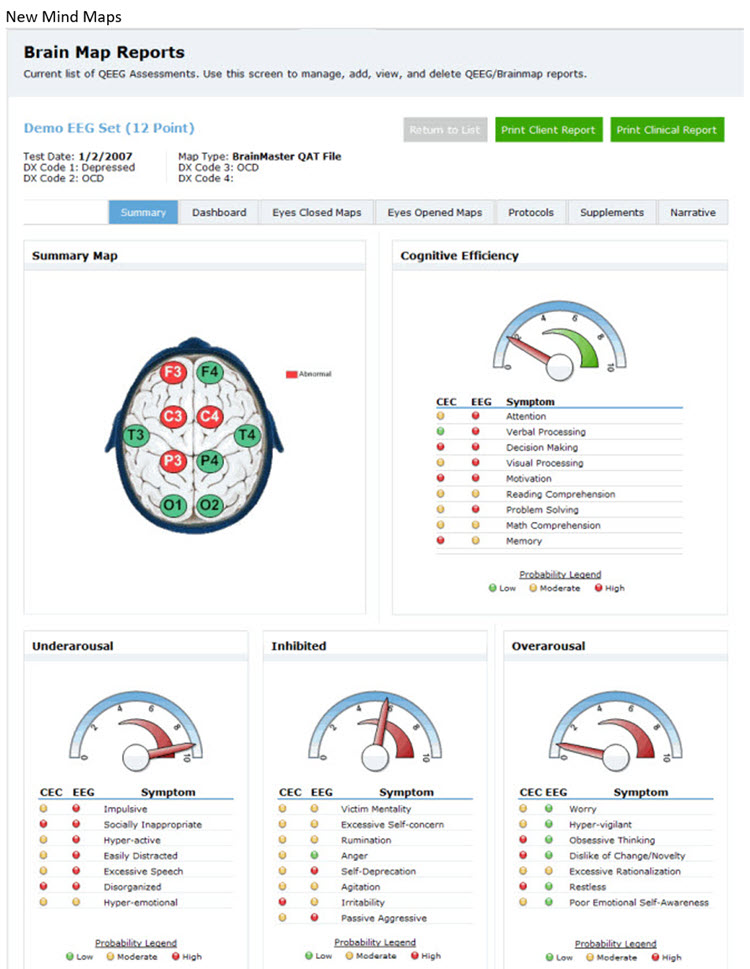

Some practitioners integrate neurofeedback with other treatment modalities they are trained to offer. These may include counseling or psychotherapy, medication management, audiovisual entrainment, brain stimulation, or peripheral biofeedback. For the latter, psychophysiological assessment can help identify which physical system to treat and provides a baseline for judging progress (Khazan, 2013; Peper et al., 2008).The quantitative data collected during intake assessment, whether from rating scales, questionnaires, cognitive tests, IQ and academic measures, or psychophysiological analysis can serve as an important baseline reference point for evaluating the effects of training and for decision-making during the course of neurofeedback.

EEG Assessment for Neurofeedback

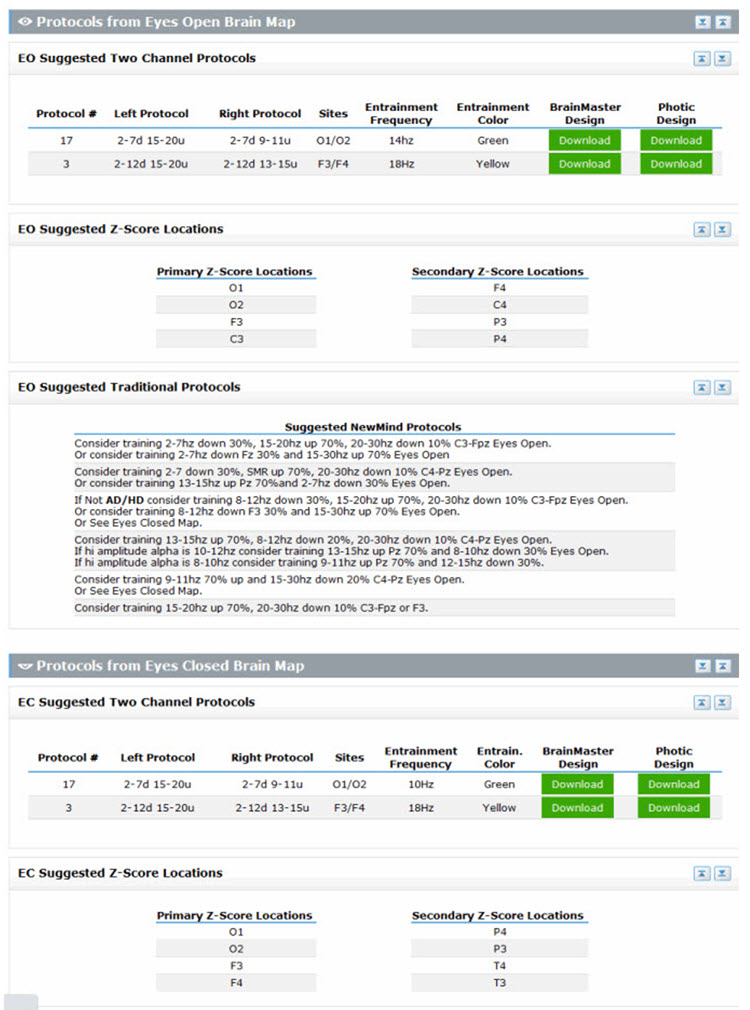

Depending on the presenting problem and goal, and practitioner training, initial EEG assessment may be more or less elaborate. The complexity of the initial evaluation also relates to the number of electrode sites used, which, in typical neurofeedback practices, ranges from one to 19.

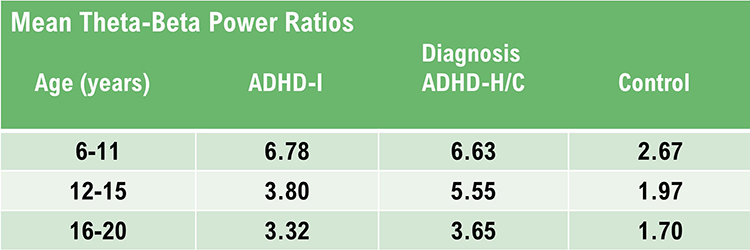

In addition to examining the analog waveform of the EEG signal, several variables can be evaluated quantitatively. Data from single sites may be represented by absolute or standardized (i.e., z-scores) values of amplitude or power in single-hertz bins or frequency bands that span a range of hertz values. Power values may also be given in ratios that compare bands.

If the practitioner uses more than one electrode for assessment, different ratios can be calculated by comparing left and right prefrontal sites or anterior and posterior sites. Sites can also be compared with variables such as coherence and phase. In cases when 19-channel records are obtained, various LORETA analyses can be performed, revealing EEG activity at Brodmann areas that are not limited to the cortical convexity. LORETA analyses enable the practitioner to examine the details of functioning in networks such as the default mode, salience, and attention networks. Normative databases are used with such analyses to compare the client’s EEG function to a healthy age-matched reference group.

Both qualitative and quantitative EEG findings are interpreted to generate hypotheses that are integrated with the information from the other components of the intake assessment.

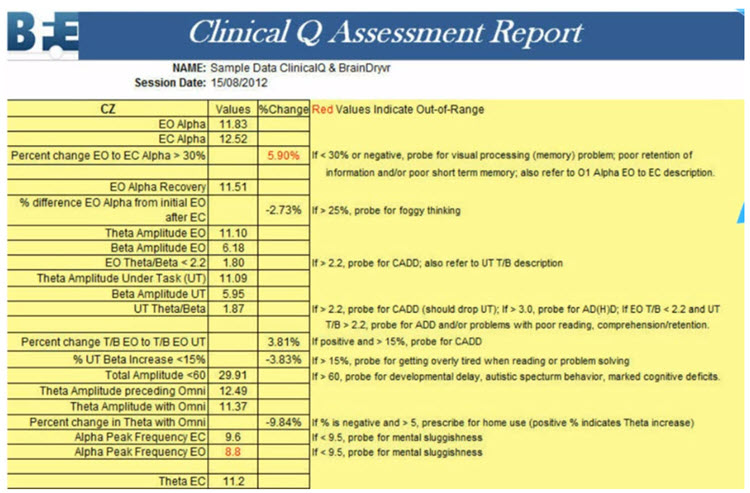

Quantitative approaches to EEG assessment include those described by Collura (2014), Demos (2019), Kaiser (2008), Soutar and Longo (2011), Swingle (2015), Thatcher (2020), Thompson and Thompson (2015), and Van Deusen (Ribas, Ribas, & Martins, 2016).

Integration of Intake and EEG Assessments

The intake assessment concludes with several necessary steps. The practitioner summarizes the critical information that has been gathered from the various assessment methods and validates this by asking the client if there is anything to correct or add. The practitioner then integrates the information with EEG findings and also with their scientific and clinical knowledge. This provides a formulation or an understanding of the problem for the client to consider. The client is then invited to share their thoughts and to ask questions.

Together with this understanding of the problem, the provider shares her or his perspective on how neurofeedback training protocols may be of use, together with the degree of scientific evidence that supports them. Details about recommended neurofeedback training are also helpful to provide. These can include a description of neurofeedback equipment, what the provider will do, what the client will do, and what the client should expect during training. Possible side-effects and how they will be addressed can be reviewed. The likely duration and costs of training should be reviewed, along with how and when progress will be monitored. Possible outcomes and durability of success can also be described.

Alternatives to neurofeedback can be reviewed, including no intervention or behavioral and lifestyle interventions. In some cases, the information collected during intake may suggest that neurofeedback is unlikely to be helpful at present. The provider considers their expertise and shares it with the client. In light of the characterization of the presenting problem, the scientific evidence, and the provider's expertise, the provider and client then consider what resources are available for treatment and review the client’s preferences. This comprehensive discussion enables the client to give well-informed consent for neurofeedback.

The provider then may conclude the assessment by determining if it is advisable to send a report and, if so, to obtain consent to do so. A time for a subsequent appointment is made. If relevant, the practitioner summarizes what the client and provider will do in the interim (e.g., self-monitoring of symptoms by the client).

Summary

The practitioner uses various methods during the intake assessment and organizes the resulting information into a summary that has utility for describing and understanding the client’s problems and goals and planning subsequent steps, including neurofeedback training. Data collected with various methods help the client make a confident and well-informed decision about whether to proceed with neurofeedback training.

Glossary

Brodmann areas: 47 numbered cytoarchitectural zones of the cerebral cortex based on Nissl staining.

collateral information: reports from family members, friends, and healthcare professionals.

cultural malpractice: assessment and treatment decisions biased by cultural insensitivity and ethnocentrism.

culturally-competent assessment: assessment that is informed by and sensitive to the meaning of actions, beliefs, and feelings within a client's culture.

evidence-based assessment: client evaluation using instruments that are reliable, valid, and possess clinical utility.

low resolution electromagnetic tomography (LORETA): Pascual-Marqui's (1994) mathematical inverse solution to identify the cortical sources of 19-electrode quantitative data acquired from the scalp.

multimethod assessment: evaluation using multiple assessment tools.

overpathologizing: labeling culturally normal behavior as abnormal.

z-score training: neurofeedback protocol that reinforces in real-time closer approximations of client EEG values to those in a normative database.

Review Flashcards on Quizlet

Click on the Quizlet logo to review our chapter flashcards.

Assignment

Now that you have completed this unit, summarize the potential benefits of collateral interviews. What can psychophysiological assessment contribute to client evaluation?

References

Bear, L., & Blais, M. A. (Eds.) (2010). Handbook of clinical rating scales and assessment in psychiatry and mental health. Springer Nature.

Collura, T. F. (2014). Technical foundations of neurofeedback. Routledge.

Conners, C. K. (2014). Conners Continuous Performance Test (3rd ed.). Multi-Health Systems.

Dana, R. H. (2005). Multicultural assessment: Principles, applications, and examples. Erlbaum.

Delis, D. C., Kaplan, E. F., & Kramer, J. H. (2001). Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. The Psychological Corporation.

Demos, J. N. (2019). Getting started with EEG neurofeedback (2nd ed.). W. W. Norton & Company.

Gaultieri, T., & Johnson, L. G. (2006). Reliability and validity of a computerized neurocognitive test battery, CNS Vital Signs. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21, 623-643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.007

Kaiser, D. A. (2008). Functional connectivity and aging: Comodulation and coherence differences. Journal of Neurotherapy, 12, 123-139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10874200802398790

Khazan, I. Z. (2013). Clinical handbook of biofeedback: A step-by-step guide for training and practice with mindfulness. Wiley-Blackwell.

Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Peper, E., Tylova, H., Gibney, K., H., Harvey, R., & Combatalade, D. (2008). Biofeedback mastery: An experiential teaching and self-training manual. Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

Pomeranz, A. M. (2020). Clinical psychology: Science, practice, and diversity (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Psychology Tools. (n.d.). Psychological assessment tools for mental health. Retrieved March 9, 2021, from https://www.psychologytools.com/download-scales-and-measures/

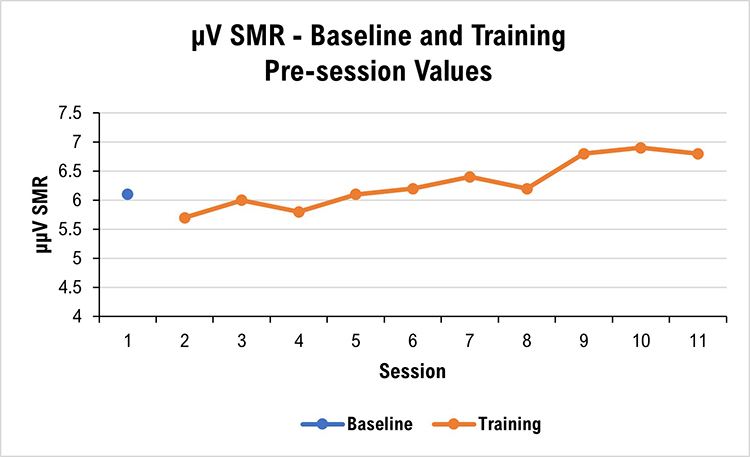

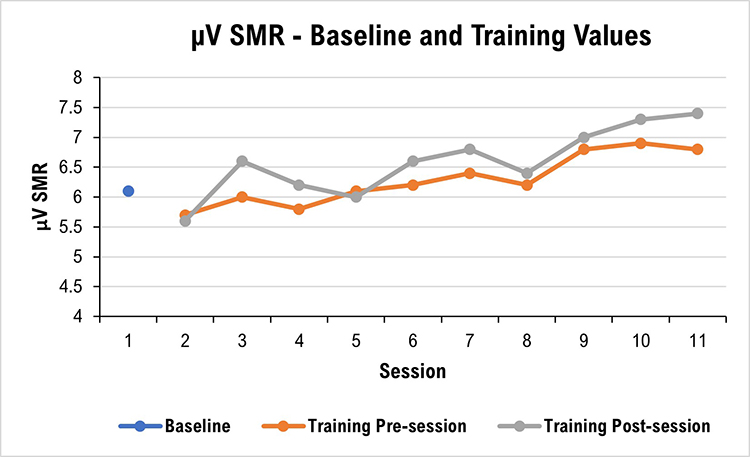

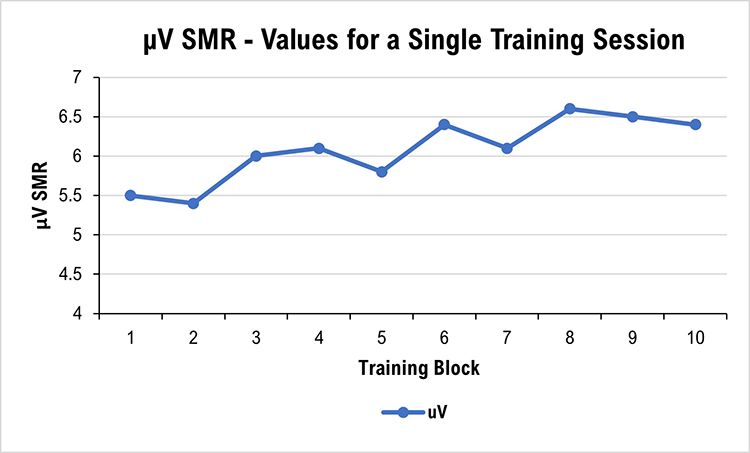

Ribas, V. R., Ribas, R. de M. G., & Martins, H. A. de L. (2016). The Learning curve in neurofeedback of Peter Van Deusen: A review article. Dementia and Neuropsychologia, 10, 98-103. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-5764-2016DN1002005

Sadock, B. J., Sadock, V. A., & Ruiz, P. (2017). Kaplan and Sadock's concise textbook of clinical psychiatry (4th ed.). Wolters Kluwer.

Schwartz, M. S. (2016). Intake and preparation for intervention. In M. S. Schwartz & F. Andrasik (Eds.), Biofeedback: A practitioner’s guide (4th ed.) (pp. 217-232). Guilford Press.

Silverman, J., Kurtz, S., & Draper, J. (2013). Skills for communicating with patients (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Soutar, R., & Longo, R. (2022). Doing neurofeedback: An introduction (2nd ed.). ISNR Research Foundation.

Stucky, J., & Bush, S. S. (2017). Neuropsychology fact-finding casebook: A training resource. Oxford University Press.

Swingle, P. G. (2015). Adding neurofeedback to your practice: Clinician’s guide to ClinicalQ, neurofeedback, and braindriving. Springer.

Thatcher, R. W. (2020). Handbook of quantitative EEG and EEG biofeedback (2nd ed.). ANI Publishing.

Thompson, M., & Thompson, L. (2015). Neurofeedback book: An introduction to basic concepts in applied psychophysiology (2nd ed.). Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback.

B. EEG/QEEG ASSESSMENT

This section covers the identification of common EEG patterns. When first looking at an EEG recording, many beginners find the visual display confusing and challenging to understand, much less to gather any useful information. This section will provide a general overview of EEG activity, identify the basic EEG rhythms and discuss behavioral characteristics associated with each type of activity. We will also discuss some of the common abnormal patterns and how to identify them. This will not provide a comprehensive picture of the EEG, and for that, further study is warranted, and guidance for such study will be provided.

Neurofeedback Tutor describes and demonstrates an example of a 2-channel assessment that uses a series of three pairs of 10-20 sites, with specific tasks for each pair. This should not be confused with an EEG assessment that uses two channels at only two assessment sites, which likely would have limited usefulness because any particular clinical complaint may be associated with deviation from the expected range at different locations depending on the individual.

Because the identification of common artifacts is covered in depth in the Artifacts section, this section will focus on true EEG activity. However, some of the similarities with certain artifacts will be addressed.

Neurofeedback is a process of identifying and training brain activity that produces the scalp electrical activity recorded by the EEG, so the practitioner must identify common EEG patterns, both normal and abnormal, to facilitate the assessment and training process.

This task has several components and begins with access to an EEG atlas. An EEG atlas is a compilation of “raw” tracings from EEG recordings, showing normal EEG patterns for various age groups and examples of typical abnormal patterns such as epileptiform activity. Examples of normal variants may appear abnormal but have certain characteristics that distinguish them from truly abnormal patterns.

There are several recommended EEG atlases, and they are listed at the end of this section. Many atlases are available, some focusing on childhood EEG, some on adult EEG, and some on the EEG characteristics of specific disorders. Those recommended in this section represent a general overview and include some components of all of the above categories.

The second step is to define normal or typical values for the EEG features so the clinician can use that information to identify training goals and help explain or elucidate causal factors related to client symptoms.

The third step is to proceed with training the client, using the same or similar assessment techniques to monitor progress and to guide any changes that may be necessary as the training progresses. Keep in mind that when making training decisions, they are often informed by identifying excesses or deficiencies at a particular scalp location within a specific EEG frequency band. This doesn’t mean that the assessment and decision-making process ends with this determination. Ongoing recognition of EEG changes, client self-reports, reports from others, and the clinician’s observations of the client will help determine any changes to the training approach.

It is important to note that training decisions must be flexible and fluid. Early in the history of qEEG guided training, some clinicians made the mistake of training to the qEEG, sometimes ignoring client reports of worsening of existing symptoms and/or the appearance of new symptoms. This is a limited and short-sighted approach to training, and the clinician must be willing to shift training if needed to obtain the best outcome. Neurofeedback is as much an art as it is a science. How much weight to give to the qEEG assessment and other assessment tools and the client’s self-report? How often is it appropriate to change training protocols? Must the clinician continue with a prescribed training even if the client reports distress? These are questions that are important to answer. This is one of the reasons that certification programs require that new practitioners participate in a mentoring relationship with an experienced practitioner, to help them provide the most effective, client-centered, dynamic training approach possible.

This brings us to a discussion of the purpose of the EEG assessment. We previously established that neurologists and electroencephalographers use the EEG to identify gross abnormalities, evidence of seizure activity, or the location of lesions in the brain. Those interested in neurofeedback-focused assessments are often interested in more subtle differences in the EEG, leading to useful guidance for training choices.

This is why there may be differences in emphasis between assessments done by a neurologist or research electroencephalographer compared to those done by neurofeedback clinicians. The focus of this section will be to help the neurofeedback clinician utilize the EEG for assessment that guides and informs the training process, including assessment of ongoing progress toward training goals.

This section covers Standardized EEG Assessments, Overview of QEEG, Normative Databases, and Recognizing Common Normal and Abnormal Patterns in the EEG.

Naming the EEG Components

Historically, the naming of the EEG frequencies followed a somewhat chaotic path (Schomer & Lopes da Silva, 2017), beginning with Berger’s (1929) designations of alpha, as the “first” rhythm and beta as everything faster than alpha.

Jasper and Andrews (1938) used the term gamma rhythm for frequencies above 30 or 35 Hz. The term gamma has become somewhat fluid in its definition, depending on the person defining it. Crick (1994) defined gamma as a frequency of 40 Hz (generally defined as 38-42 Hz or 36-44 Hz with a center frequency of 40 Hz), as did Sheer and colleagues (1992). Others, such as Davidson and colleagues (2004), used the frequency band 25-42 Hz to represent gamma, and Swingle also used the term to denote faster beta activity above 25 Hz. Amzica and Lopes da Silva (2017) also used the term gamma to define a frequency of 30-50 Hz. St. Louis and Frey (2016) stated that frequencies from 25-70 Hz are called low gamma, while those above 70 Hz represent high gamma. These sometimes conflicting definitions can lead to confusion as to the precise meaning of this term

Walter (1936) chose the term delta to represent all the frequencies below the alpha band and later added the term theta to identify the portion in the 4-7.5 Hz range. Currently, these terms remain fairly well defined, with delta representing 1-4 Hz and theta representing 4-7 or 4-8 Hz.

Following the naming of these five frequency bands, many other electroencephalographers have sought to name EEG patterns, sometimes choosing names for patterns that already have descriptive designations, such as the pattern known as positive occipital sharp transients of sleep with the acronym POSTS also being called rho waves and posterior slow rhythms of 3-4 Hz being called the pi rhythm. These two terms and several others have fallen out of favor. Schomer and Lopes da Silva (2017) suggest that the use of Greek words to identify EEG activity should be confined to the classic bands of alpha, beta, gamma, delta, and theta. As we will see in our alpha and beta frequencies discussions, the mu rhythm is one exception to this restriction.

A lack of precision in terminology makes numerical designations a better choice for defining EEG observations. This ensures that one’s meaning is clear when speaking of an EEG frequency band. Adding the location and the client’s state (eyes open, eyes closed, asleep, etc.) provides the necessary detail for communicating one’s findings to others. Therefore, describing eyes-closed 8-12 Hz activity, with a dominant frequency of 10 Hz and amplitude between 20-30 uV, in specific occipital and parietal sensor locations, is quite useful for assessment purposes instead of a general finding of “posterior alpha.”

Before proceeding further with the discussions of individual frequencies, it is important to note that brain activity in general and more specifically the scalp EEG patterns that reflect that brain activity are organized and regulated by multiple cortical, sub-cortical, and general network mechanisms. One of the most important mechanisms is cross-frequency synchronization (CFS), which describes waves of one type of frequency, such as beta or gamma, occurring synchronously with the wave patterns of slower frequencies such as delta, theta or alpha. These are often described as nested rhythms. Siebenhuhner and colleagues (2021) propose that cross-frequency synchronization “integrates processing among synchronized neuronal networks from theta to gamma frequencies to link sensory and attentional functions.”

When considering the activity of individual EEG frequencies, it is important to recognize how they interact, how they are interdependent, and how they reflect the activity of the broader neuronal networks in the brain, central nervous system, and the organism as a whole. The EEG does not cause behavior. Instead, it reflects behaviors that have already happened or are currently occurring and are the result of a highly complex dance of interactions.

8-12 Hz EEG – the Alpha Rhythm

Due to alpha being the first EEG pattern to be identified historically, we will begin by defining the alpha rhythm. The International Federation of Societies for Electro-encephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology (IFSECN) (1974) offered the following definition:

Rhythm at 8 to 13 Hz occurring during wakefulness over the posterior regions of the head, generally with higher voltage over the occipital areas. Amplitude is variable but is mostly below 50 μV in adults. Best seen with eyes closed and under conditions of physical relaxation and relative mental inactivity. Blocked or attenuated by attention, especially visual and mental effort.

Such a rhythm must meet all the above criteria to qualify for the designation, eliminating patterns such as mu rhythm in the Rolandic areas, which often has the same frequency but different morphology (characteristic wave shape and pattern) and behavioral correlations.

Source of 8-12 Hz Alpha Activity

Activity in the 8-12 Hz frequency range appears associated with reduced sensory and cognitive activity. Why is this so? What mechanism is responsible for this rhythmic activity?

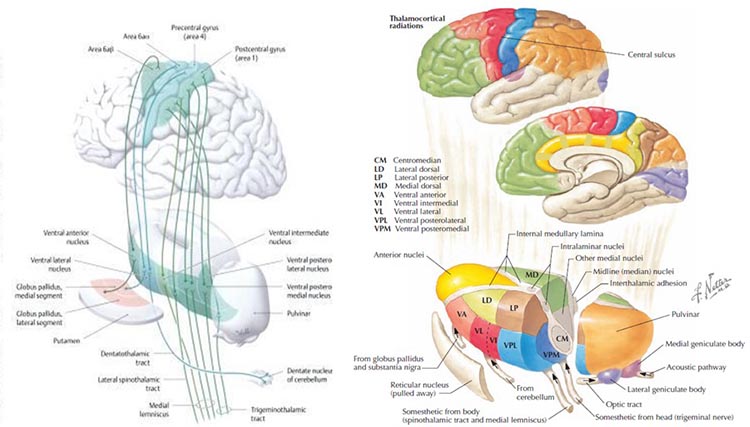

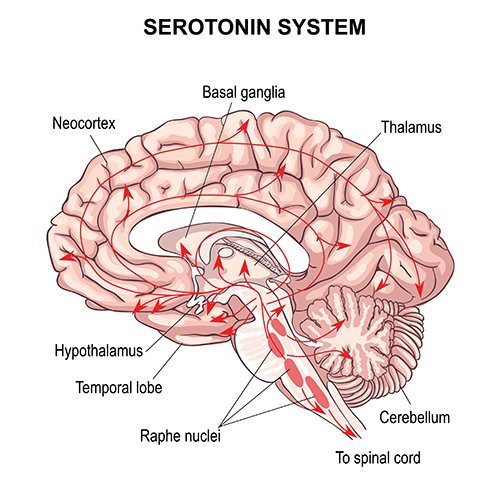

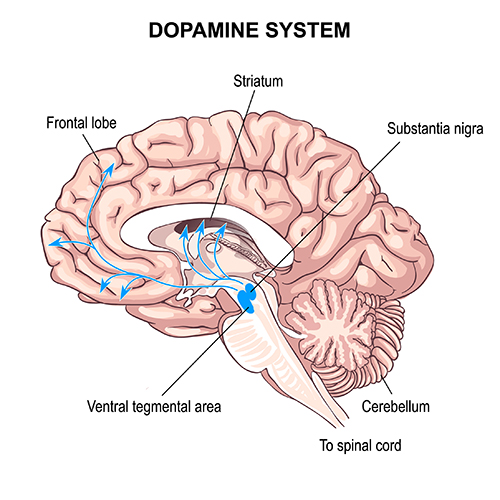

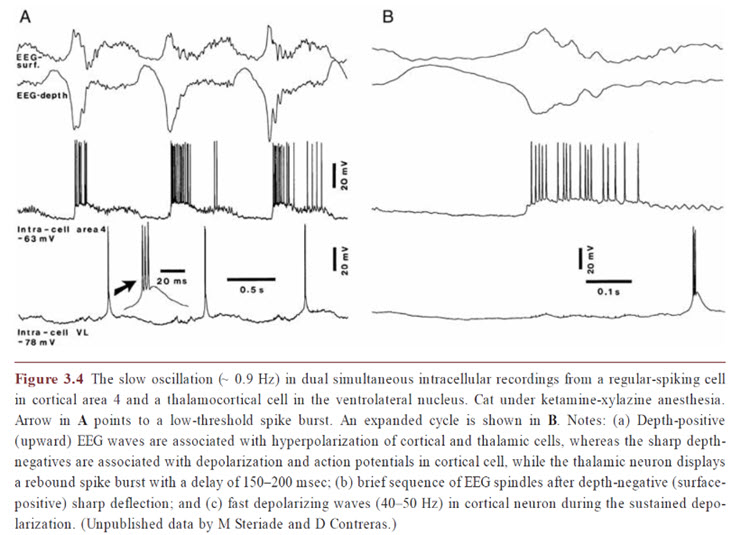

One of the main communication pathways between the external world, the senses that perceive and transmit this information, and the cortical neurons that receive it, is the thalamic-cortical relay system, often designated the TCR system. The thalamus receives incoming sensory input (a paired structure in the brain's center – see the image below). The individual nuclei of the thalamus transmit that sensory information to appropriate areas of the cortex. The occipital and parietal areas of the cortex are the primary visual processing areas, just as the temporal areas process most of the auditory information. In contrast, central Rolandic areas process tactile and other signals from the skin and muscles. Of course, current findings indicate that brain activity is associated with coordination within and between cortical networks and influences from subcortical structures and local and TCR influences. Still, the TCR system is a primary pathway for determining which areas of the cortex receive each type of sensory input. Thalamic-cortical relay system graphic © Elsevier Inc. - Netterimages.com.

When the eyes close, the neurons responsible for processing incoming visual information no longer have “ work” to do, and so they respond to another signal coming through the TCR system. This is a rhythmic signal mediated by a membrane of inhibitory GABAergic neurons that surround most of the thalamus and provide inhibitory regulation of the signals traveling to the cortex. This is called the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (TRN) or nucleus reticularis of the thalamus (NRT). The function of this system is much too complex for this section, but a good treatment is available in Crabtree (2018), and an examination of the role of the TCR and TRN systems in consciousness is found in Min (2010).

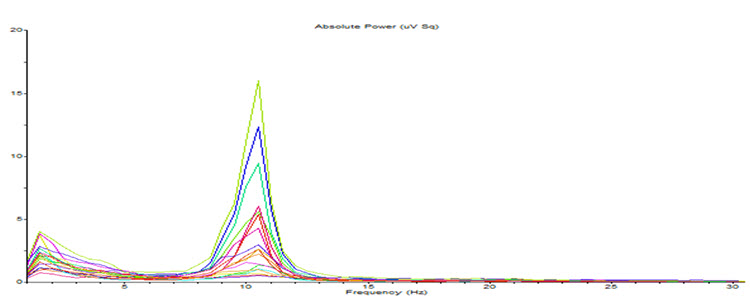

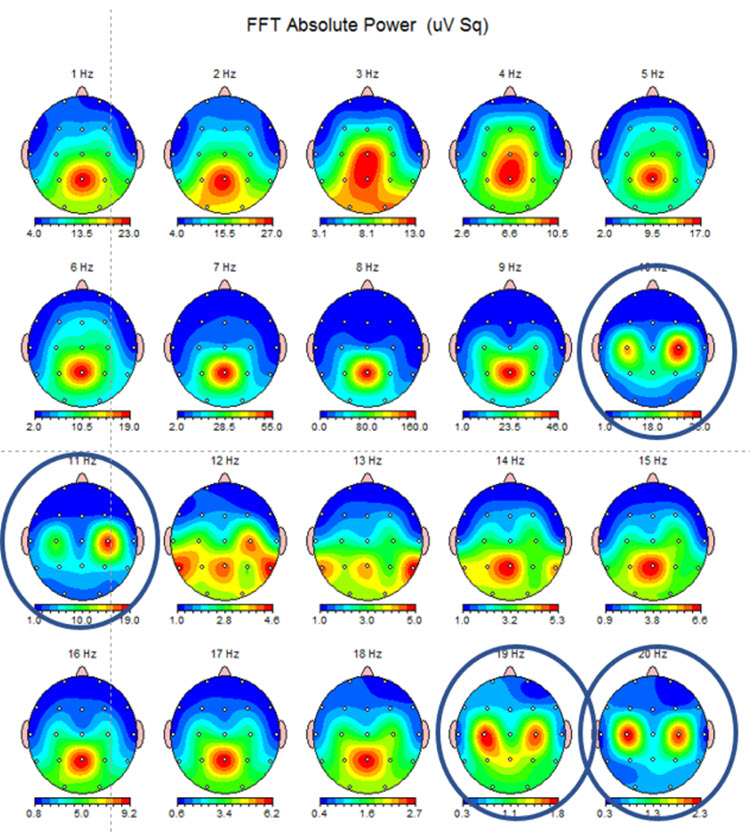

The rhythmic signal from the TCR and NRT interaction produces a 10-Hz (8-12 Hz range) input to the visual processing neurons when visual sensory input is withdrawn (eyes closing), resulting in those neurons firing synchronously in that frequency in response to this input. The voltage of a specific EEG frequency, measured at the scalp surface, is directly proportional to the number of cortical neurons firing synchronously in that frequency (Nunez & Srinivasan, 2006). Therefore, when the eyes are closed, and the signal from the TCR system changes from sensory input to a rhythmic 10-Hz input, visual neurons respond to that input and the voltage of alpha, and most specifically in adults, 10-Hz activity increases in voltage. The image below shows a spectral display of an eyes-closed EEG.

Note: eyes-closed EEG in longitudinal bipolar montage represented as a spectral display. The x-axis shows frequency from 0-30 Hz, and the y-axis shows absolute power (uV Sq). Note the peak at about 10 Hz. Voltage is higher in the P3-O1 derivation than in the P4-O2 derivation, revealing a small asymmetry. The highest power is in the T4-T6 derivation.

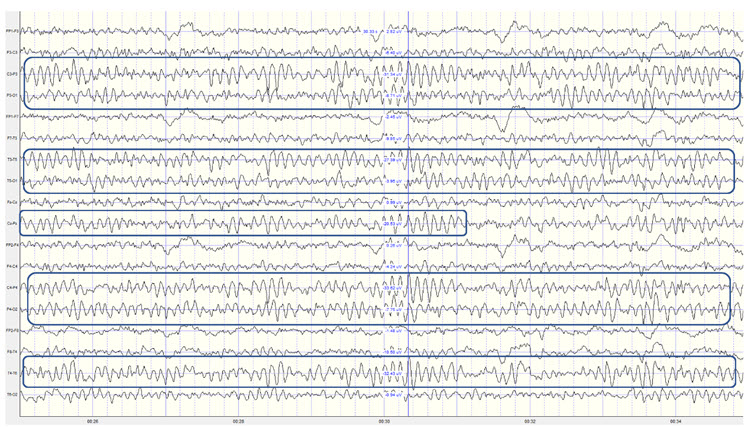

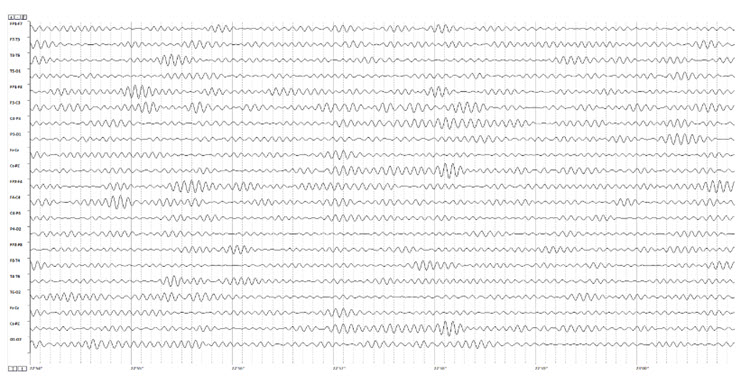

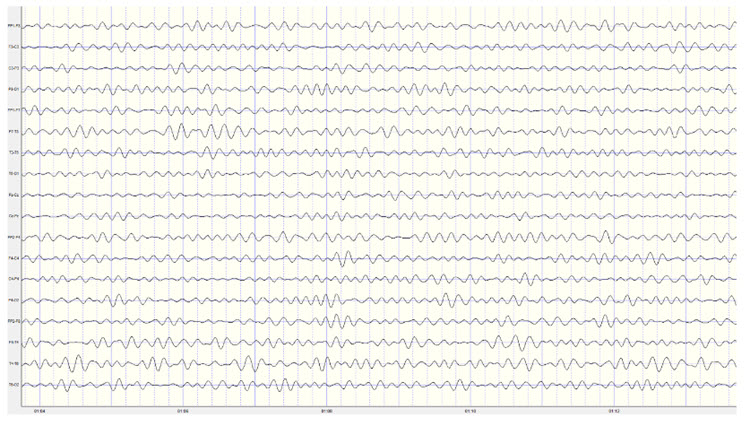

Identifying alpha activity in parietal and/or occipital areas of the scalp is usually quite easy, particularly in the eyes-closed condition. The image below shows an eyes-closed alpha pattern from a 15 -year-old male.

Note: eyes-closed EEG filtered to 1-45 Hz in the longitudinal bipolar montage with a 50-uV scale. Boxes indicate the most prominent 8-12 Hz activity. This montage represents a series of adjacent electrode comparisons or derivations, as each signal tracing is derived from each pair of electrode comparisons.

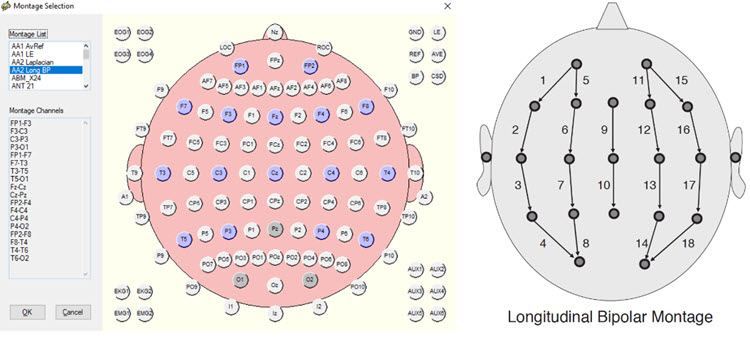

This longitudinal bipolar montage is displayed below.

Note: longitudinal bipolar montage (commonly known as the “double banana” montage). Note the arrows in the right-hand image indicating the sequence of pair-wise comparisons. Various sequences have been used.

Observe that the rhythmic activity is well-defined and has the typical bursting or spindling pattern of the alpha rhythm, resulting from the input of the TCR and NRT systems. Spindling consists of a series of distinct oscillations of a particular frequency that begin with relatively low amplitude, increase in amplitude, and then decrease in amplitude, giving the appearance of a spindle such as one used in spinning, with fiber wound around it. Graphic © New africa/Shutterstock.com.

The waves are quite sinusoidal (waving up and down in a smooth rhythm similar to a sine curve) and continue throughout the recording with minimal disruption. The voltage indicator shows that the maximum voltage at the moment of the line placement was from about 20 to 30 uV at the peak of the waveform in this montage.

One can determine the wave's frequency by either counting the number of peaks in a one-second segment or counting the number of times the wave crossed the zero line and dividing by 2 (zero crossings/2). Either method gives a 8-9 Hz value when multiple one-second epochs are counted. This is somewhat slow for a 15-year-old, although the voltage appears to be within normal limits. When compared to a normative database, we can see that indeed, it is a slow peak alpha when compared to other 15-year-old males as indicated by the chart below from the NeuroGuide database:

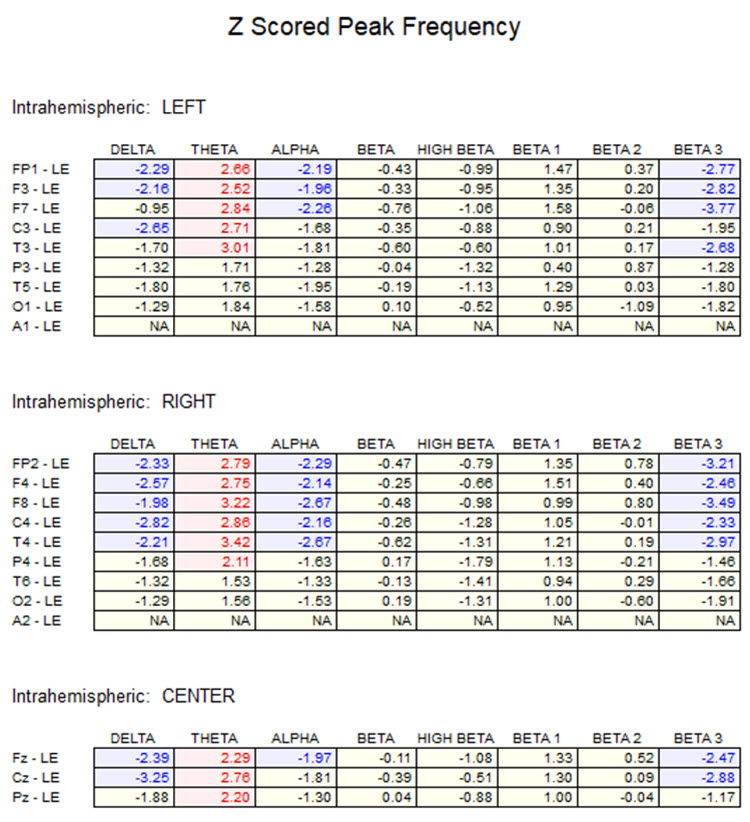

Note: the alpha peak frequency z-scores are at least 1 SD below expected values (> -1.0 SD) in all locations and many areas show deviations exceeding the significance cutoff of -1.96 SD (blue highlight). The database also plots the theta peak frequency as fast (red highlight) due to slow alpha in the 8-Hz frequency bin or segment. There are likely other slow components of the dominant rhythm that contribute to this incorrect plot of the frequency information. Ideally, the peak frequency of the EEG should be calculated within a broad range from approximately 6 Hz to about 14-16 Hz to avoid this type of error. This is another problem with the somewhat arbitrary designation of frequency bands using set values.

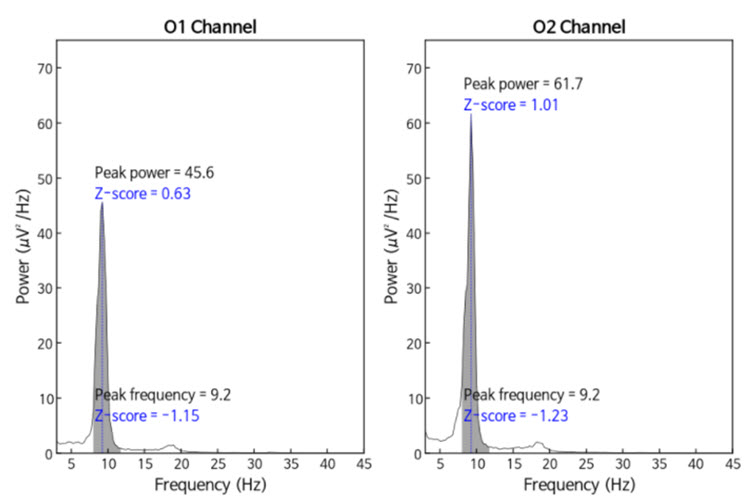

The same data processed by the iSynchBrain database show similar findings for O1 and O2 below:

Note: peak frequency power and frequency comparisons at O1 and O2 showing slow peak frequency at 9.2 Hz bilaterally, resulting in z-scores of -1.15 and -1.23, respectively, with voltage (power) on the left at 0.63 SD and on the right at 1.01 SD, showing slightly elevated values. This database provides single-Hz calculations for both frequency and amplitude rather than using an arbitrary band to define alpha.

The alpha peak frequency is age-dependent, though not called ” alpha” until the frequency reaches 8 Hz. In early infancy, it is designated as the posterior basic rhythm or posterior dominant rhythm (PDR). It appears around the age of 4 months with a frequency of about 4 cycles per second (c/s) or Hz (Schomer & Lopes da Silva, 2017). The PDR increases (speeds up) during maturation and is approximately 6 c/s at 1 year and up to 8 c/s at around 3 years of age. This is when it can be called the alpha rhythm.

The frequency reaches 10 Hz by approximately 10 years of age, and that (10.2 ± 0.9/sec) is the peak frequency of adulthood (Petersén & Eeg-Olofsson, 1971). From the previous example, we see why a peak frequency between 8-9 Hz is slow for a 15-year-old.

Meaning and Importance of the Alpha Peak Frequency

The speed or frequency of the alpha peak frequency is often mentioned, even in a neurologist’s report. For the neurofeedback practitioner, it is helpful to understand the factors associated with different alpha frequencies. The alpha peak frequency is a measure of the frequency of the rhythmic pattern of the posterior rhythm (generally called alpha). This has traditionally been an important measure. Although it has recently been somewhat de-emphasized in some EEG circles, it remains an interesting measure. It has a great deal of research supporting it as a useful metric for assessment.

A slow peak alpha frequency has been associated with some forms of cognitive decline and memory impairment (Stam, 2017) as well as mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI; Jabbari et al., 1985; Williams, 1941). A fast peak alpha frequency has been associated with improved scores on timed IQ tests. It has also been associated with enhanced memory and cognitive performance in various age groups (Grandy et al., 2013). A faster peak alpha frequency is associated with advanced reading skills in precocious children (Suldo et al., 2001).

The peak alpha frequency changes through the lifespan. Therefore, age-normed values for the peak alpha frequency are important for assessment purposes. The normal adult peak alpha frequency is 9.5-10.5 Hz. Jabbari et al., 1985 Scholarly literature states that the peak alpha frequency is not abnormal until it is below 8 Hz (Schomer & Lopes da Silva, 2017). However, it is commonly thought to be potentially meaningful when the frequency is below 9 Hz for an adult.

Stam (2017) stated that slowing the alpha peak frequency by more than 1 Hz (9 Hz for an adult) is generally a sign of pathology. A slow alpha frequency can be associated with fatigue, cognitive decline, and memory impairment. Slowing of the background alpha rhythm is also a sign of generalized cerebral dysfunction (Nayak & Anilkumar, 2021). Rathee and colleagues (2020) related the speed of the peak alpha frequency to reading comprehension. They found that a slower peak alpha frequency is associated with poor comprehension.

Negative correlations of a peak alpha frequency faster than 10.5 Hz, possibly associated with an overly activated central nervous system, may include sleep initiation problems, anxiety, intrusive thoughts, and difficulty with self-soothing and self-calming skills.

Meaning and Importance of the Eyes-Closed Alpha Response Voltage

In addition to the peak frequency within the 8-12 or 8-13 Hz alpha band, the amplitude of the activity can also be meaningful. The alpha voltage will be partially affected by the montage that is used. For example, keeping in mind the discussion of differential amplifiers in the Instrumentation and Electronics section, the closer two electrodes are to each other, the more the rhythmic, synchronous patterns will be attenuated. Common-mode rejection (CMR) is most sensitive to frequency synchronization, so waves that are the same frequency and also synchronous (e.g., 10 Hz waves, waving up and down at the same time at the two sensor locations + and – [also commonly called “active” and “ reference”]) will be rejected. Comparing the O1 and O2 occipital electrodes to each other will result in a lower apparent voltage of alpha if the two waveforms are synchronous, which is quite likely.

Conversely, comparing either O1 or O2 to an ear reference or possibly to a forehead reference would result in almost no rejection of alpha activity. Therefore, the rhythmic patterns are unlikely to be similar at these distant locations and will be retained. When viewing standard voltage information in an atlas or a research paper or textbook, try to identify the montage used when those standards were developed.

Simonova et al. (1967) found amplitudes between 20 and 60 μV in 66% of their subjects, while values below 20 μV were found in 28% and above 60 μV in only 6%. Schomer and Lopes da Silva (2017) suggest that values between 10 and 60 μV are typical. However, other sources such as the John Hopkins Atlas of EEG (2011) and Libenson’s Practical Approach to Electroencephalography (2009) cite 20 μV as the minimum voltage for adults. These differences may seem insignificant but can represent the difference between a low voltage fast EEG finding and a typical assessment.

Rhythmic alpha activity represents the synchronization of the EEG. It represents part of the excitation/inhibition cycle. When either large or small groups of neurons perform tasks, this results in the desynchronization of the EEG during work, as each group of neurons performs its function somewhat locally and somewhat independently. This is followed by a resting or inhibitory phase that results in the synchronization of the EEG and hence an increase in alpha amplitude as many neurons fire synchronously. This is clearly seen in the shift from active visual processing when the eyes are open to a synchronous pattern of oscillatory activity when neurons do not have incoming visual input to process and can rest. This measure of alpha voltage change from eyes open to eyes closed, known as the alpha response, and the decrease of alpha with eyes opening, called alpha blocking, helps identify if the work/rest cycle is occurring correctly.

Someone with an eyes-closed posterior dominant rhythm voltage below 20 μV suggests to the neurofeedback assessor that the person does not easily shift to a state of decreased arousal/alertness necessary for alpha amplitude to increase. The disconnection from the outside world upon eyes closing should result in decreased sensory processing of vision and other senses and decreased cognitive activity, leading to an increase in 8-12 Hz amplitude or power.

Typically, alpha activity voltage should increase as more neurons fire synchronously in this frequency. When this increase is less than 50% above the resting baseline eyes-open alpha voltage, it usually indicates some difficulty turning off the mind, meaning that neurons remain activated and working and thus prevented from entering a resting state. The lack of a typical alpha increase may be associated with heightened states of alertness and vigilance, meaning that these clients maintain their external perceptive focus and/or cognitive activity, even when the eyes are closed, likely meaning that the ability to achieve global synchronous activity is being inhibited. Resulting behavioral consequences can include fatigue, as the neurons are constantly engaged and are not allowed to rest. This pattern may be associated with a history of trauma and/or a history of hypervigilance for various reasons.

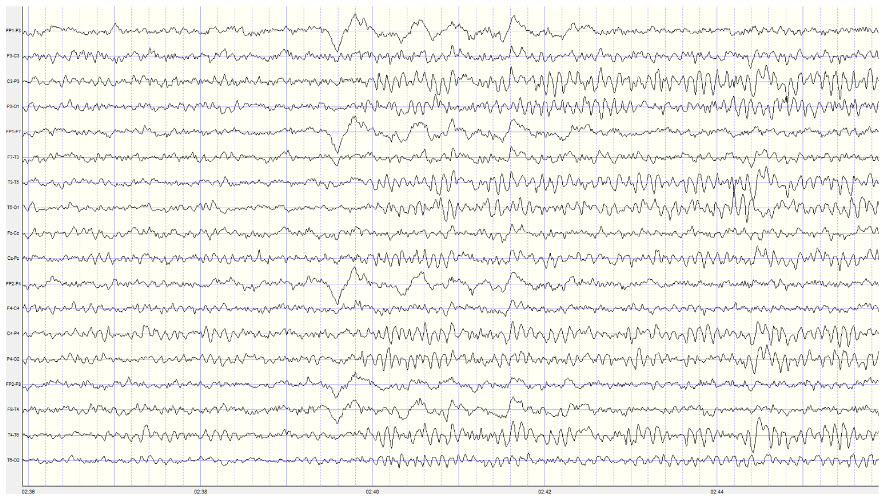

Example of a typical alpha response upon eyes closing:

Note: this is a 19-channel recording of the transition from eye-open to eyes-closed conditions. This is a longitudinal bipolar montage, and the scale is 50 μV. Note the eyes closing at minute 2:40 (indicated by the eye movement) and the immediate response of the alpha rhythm appearing.

Meaning and Importance of the Alpha Blocking Response

Conversely, the continued presence of alpha once the eyes are open suggests a lack of appropriate alpha blocking. This appears to result from a lack of inhibition of synchronous generator mechanisms. Hartoyo and colleagues (2020) showed a simple mechanism: excitatory input to inhibitory cortical neurons. This differs from the excitatory cortical neurons that typically reduce synchronous cortical firing in favor of local responses to incoming stimuli when the eyes are opened.

Note that activation of inhibitory mechanisms results in increased inhibition, even though the function is initially excitatory. Conversely, activation of excitatory mechanisms results in greater activation. This can seem confusing, and it may help to focus on the result, whether excitatory or inhibitory, rather than the initial behavior.

There should be a dynamic balance between excitation and inhibition in the human neocortex (Dehghani et al., 2016). When this balance is disrupted, we see the behavioral effects noted here. Alpha blocking represents the re-activation of visual processing neurons when visual input returns. Typically, as these neurons are no longer in a common or general resting state but are involved in task-oriented behaviors that are more localized, synchronous activity should decrease (be inhibited). Therefore, the overall voltage will decrease because of less synchronization. This does not imply that more neurons are firing when alpha amplitude is higher; it means less synchronization and hence lower voltage.

Imagine an auditorium full of people initially clapping synchronously (eyes-closed alpha rhythm). The noise is loud because everyone is clapping at the same moment (higher amplitude) and completely quiet in between claps, and the frequency of the claps reflects that synchrony. Then, imagine everyone clapping independently, possibly in synchrony with immediate neighbors but not with the audience as a whole. This is like the eyes-open condition and, though there will always be some noise, because someone is always clapping, resulting in a faster frequency of clapping. At no one moment will it be as loud as when the entire audience clapped synchronously. So, the overall voltage is lower even though the frequency of clapping is faster. Thus, alpha amplitude decreases when the eyes are opened, and this should occur quickly, in 1-2 seconds and certainly in less than 10-15 seconds. Any delay in alpha blocking suggests difficulty returning to the task. Desynchronization of the EEG occurs in posterior areas as visual processing begins when the eyes are opened.

The most common reasons for the lack of appropriate alpha blocking (meaning alpha activity persists after eyes are opened) are:

1. Fatigue, including sleep deprivation

2. Long-term meditation practice, particularly mantra meditation

3. Marijuana use and abuse, generally long-term, chronic

4. Cerebral dysfunction due to disease, injury, or possibly chemical exposure

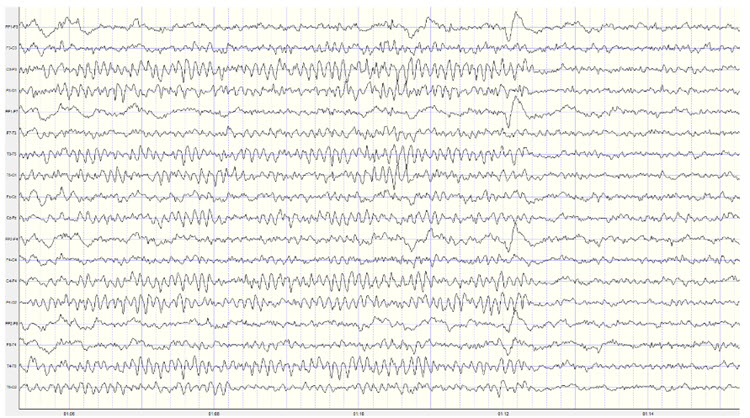

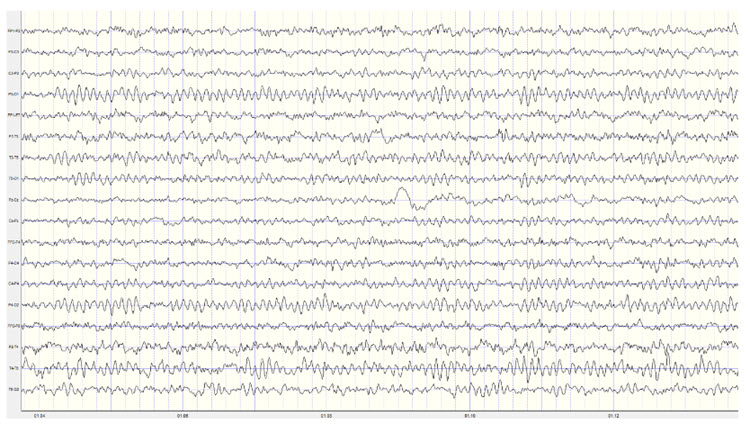

Below is an example of correct alpha blocking following the eyes opening:

Note: this is a 19-channel recording of the transition from eyes-closed to eyes-open conditions. This is a longitudinal bipolar montage, and the scale is 50 μV. Note the eyes opening at minute 1:12 (indicated by the eye movement) and the immediate blocking of the alpha rhythm.

Clearly, the response of 8-12 Hz EEG activity can be quite revealing and provides the clinician with helpful information about the client. However, it is important to note that other factors can affect the EEG recording. We have already noted the effects of artifacts on the EEG generally. Additionally, the client’s state of mind, level of anxiety, comfort with the application of sensors to the scalp, level of trust of the practitioner conducting the recording, amount of sleep, the use of caffeine and other stimulants and common medications can all affect the results of the recording.

Once an assessment is made of excess or deficient alpha activity, lack of an alpha response or persistent alpha following the eyes opening, or a slow or fast peak alpha frequency, the clinician can proceed with training to address these findings. There are multiple approaches to training the 8-12 Hz frequency band, including training specific segments of that band to achieve training goals. For example, if a lack of an alpha response to eyes closing is associated with anxiety and possibly insomnia, training for an increase in the 8-10 Hz portion of the posterior alpha rhythm in the eyes-closed condition may be an effective intervention. If the peak alpha frequency is slow, training for increases in the 10-12 Hz portion may help speed up this frequency. If there is persistent alpha in the eyes-open condition, inhibiting or downtraining 8-12 Hz generally may be helpful.

Of course, with any intervention, other causal factors must be addressed as well. Persistent alpha and/or frontal alpha can signify fatigue secondary to a sleep disorder such as sleep apnea. Therefore, a referral to a physician for a sleep study may be helpful. Over-arousal patterns that correspond to a lack of alpha response can be associated with a history of emotional, psychological, physical, or sexual trauma. These issues may need to be addressed by the neurofeedback clinician or by referring the client to an appropriate therapist.

13 or 14 to 25 or 30 Hz EEG – the Beta Rhythm

The following description is from Kane et al. (2017):

Beta band: Frequency band of 14–30 Hz inclusive. Greek letter: β.

Beta rhythm or activity: Any EEG rhythm between 14 and 30 Hz (wave duration 33–72 ms). Most characteristically recorded over the fronto-central regions of the head during wakefulness. The amplitude of the fronto-central beta rhythm varies but is mostly below 30 µV. Blocking or attenuation of the beta rhythm by contralateral movement or tactile stimulation is especially obvious in electrocorticograms. Other beta rhythms are most prominent in other locations or are diffuse and may be drug-induced (for example, alcohol, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and intravenous anesthetic agents).

Beta activity appears to result from multiple factors associated with active patterns organized by slower rhythms. Bursts of beta occur in frontal-central, frontal-temporal, frontal-parietal, and central-parietal areas and are associated with different tasks based upon the structures underlying these areas. Because all functions are distributed to multiple sites, it is difficult to precisely define which part of the CNS is responsible for each function. The observations in this section are based on both animal and human studies, the latter primarily in lesion studies and during neurosurgery.

Beta is also associated with the negative shift of the DC gradient (Speckmann et al., 2017). The DC gradient, only measurable by a DC-coupled EEG amplifier, measures the overall electrical gradient of cortical areas under the recording sensors. This gradient shows a slow oscillation of less than 1 second and is usually in the 0.1-0.2 Hz range. A shift of the gradient from its current state, becoming more electrically positive or negative, occurs every 5-10 seconds and sometimes quite a bit less often. Buzsaki (2011) states that there is a progression of frequencies whose bandwidths overlap and interact with each other, from frequencies that take 15-40 seconds to complete each cycle up to those that oscillate at 200-600 cycles per second. Gunkelman (2005) called beta and gamma activity “emergent properties of bound networks.” This means that, as slower frequencies of EEG synchronize across networks, beta and gamma emerge in bursts of activity in coordination with that synchrony.

Beta activity is associated with "work" and reflects the ongoing excitatory/inhibitory cycles occurring on multiple time scales. While the work/rest cycle mentioned in relation to the alpha response and alpha blocking is one type of excitatory/inhibitory cycle on a broader scale, beta activity reflects actions that occur millisecond by millisecond and appear to be more locally generated.

Beta frequencies have a relatively low voltage compared to slower frequencies. As noted in the above definition, amplitudes are generally less than 30 μV and frequently less than 20 μV. Remember our example of the audience clapping. In the example below, “clapping” occurs more often but with less power due to less synchronous activity.

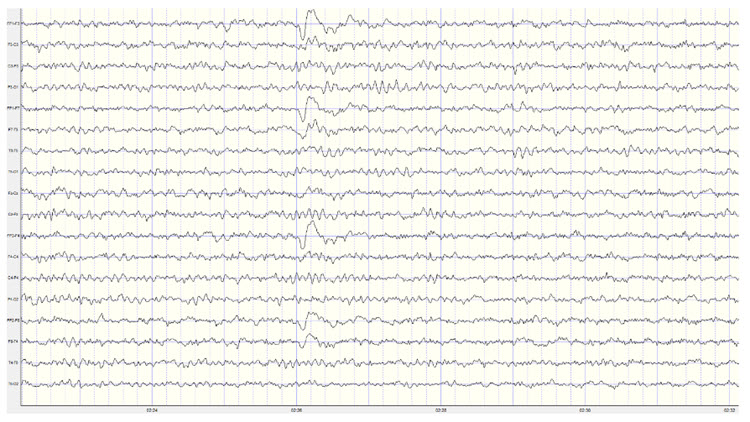

Below is an example of eyes-open beta activity:

Note: this is a 19-channel EEG recording in the eyes-open condition. This is a longitudinal bipolar montage, and the scale is 50 μV. Observe the alpha activity continuing at a much lower voltage in parietal and occipital derivations, compared to the previous eyes-closed examples, resulting from the attenuation of alpha with the opening of the eyes. There is beta activity in the 20-30 Hz range at less than 10 μV, seen mostly in frontal, central, parietal, and temporal derivations (comparisons between adjacent sensors) and somewhat slower 15-20 Hz patterns.

Kropotov (2016) describes the existence of several beta rhythms with different frequencies, various locations, and distinct functions. From this information, he states that there is likely no single neuronal mechanism for generating localized beta activity. This fits with the understanding that beta activity is associated with local tasks and therefore is mediated more by local mechanisms, all with overall coordination from network systems and other rhythmic activity.

When beta activity is typical for the client based on age, state (eyes-open, eyes-closed, under task, etc.), and location, it suggests that those areas are functioning as expected. If beta activity is deficient, that may mean that the site is under-functioning or under-activated for some reason. Reasons may include damage of some sort, metabolic deficits, fatigue, or other factors. An area that is consistently over-functioning may, in time because of overuse and fatigue, end up with a lower level of functioning and hence less beta activity.

Higher-than-typical beta amplitude at a given location may mean that the area is over-functioning or overly activated. Whether the beta amplitude is higher or lower than average, the clinician will want to understand the underlying functional neuroanatomy of the area to aid in the assessment process. For example, suppose the right posterior temporal/parietal junction that roughly underlies the area between T4 and T6 (TP8 in the 10-10 system) shows excess beta amplitude. In that case, it may be associated with heightened sensitivity to or attention to non-verbal communication such as tone of voice, facial expression, and body language associated with angry outbursts or that may signal danger. If this area is under-activated, it may represent a self-protective “disconnection” from these same signals (Gunkelman, 2021).

Individuals who typically show excess beta activity at sleep onset and during sleep stages have a higher incidence of insomnia (Perlis et al., 2001). Meier and colleagues (2014) found a correlation between excess beta power in frontal, central, and temporal areas with delinquent behavior in adult men with concurrent ADHD symptomatology. In Rowan’s Primer of EEG (2nd ed.), Marcuse and colleagues (2016) identify excess interhemispheric beta asymmetry as an important diagnostic tool. The side with reduced relative beta power points to the pathological hemisphere. They identify brain abscesses, stroke, tumor, vascular malformations, and cortical dysplasia as associated with a focal decrease or enhancement of beta activity.

A reference to a normative database can be useful when assessing beta activity, particularly if a traumatic brain injury is suspected. Comparison with other EEG frequencies is also important, as an excess or lack of beta activity is often accompanied by differences from expected values for other frequencies.

Rhythms with Similar Frequencies But Different Characteristics – Not Beta

There are a few special cases where activity in the supposed beta frequency range may represent other EEG patterns. One important example is a rhythmic pattern seen over the sensory-motor cortex, generally at C3 and C4, known as the mu rhythm. This rhythm has a frequency of between 10-15 Hz and, therefore, may be mistaken for alpha or beta activity. Kane and colleagues (2017) describe the mu rhythm as follows:

Mu rhythm: Rhythm at 7–11 Hz, composed of arch-shaped waves occurring over the central or centro-parietal regions of the scalp during wakefulness. Amplitude varies but is mostly below 50 mV. Blocked or attenuated most clearly by contralateral movement, the thought of movement, readiness to move or tactile stimulation.

Greek letter: μ. Synonyms: rhythm rolandique en arceau, comb rhythm (use of terms discouraged).

The mu rhythm can occur with a frequency over 13 Hz and can have spectral peaks in alpha (8-13 Hz) and beta (14-25 Hz) frequency bands (Jenson, 2020) and hence appear in either the alpha or beta frequency bands in quantitative EEG analysis. Mu can also show an additional characteristic, known as a harmonic effect in the EEG recording (Cheyne, 2013; Jones et al., 2009). It usually manifests as a peak in a spectrograph at twice the frequency of the mu rhythm. So, a 10-Hz mu rhythm would often have a 20-Hz pattern associated with it, whereas a 13-Hz mu rhythm may show a 26-Hz harmonic.

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies by Jones and colleagues (2009) show that what they call mu-alpha (mu rhythm in the alpha frequency range) and mu-beta (mu rhythm in the beta frequency range) co-occur at a rate greater than chance, suggesting similar mechanisms associated with their presence in the recording. They also show that this activity is not an artifact of the recording process but that it is more difficult to differentiate the faster beta component when using EEG instead of MEG. MEG studies have demonstrated that beta frequency activity originates in precentral locations and alpha frequency activity in post-central locations (Hari et al., 1997).

Below are two examples of mu rhythm activity as a tracing with a 19 channel recording and as a topographic representation of the same data.

Note: this example shows a mu rhythm with the typical negative-going wave (up in this example) appearing somewhat rounded and the sharp positive-going wave (down) at C3 and C4. This is a Laplacian montage with a scale of 300 uA (microamperes). Counting the frequency yields a mu rhythm of 10-11 Hz.

Note: this example shows the same EEG data in a topographic display showing the 10-11 Hz mu activity at C3 and C4 and the double harmonic at 19-20 Hz in the same locations. This is often referred to as the “owl eye” display because the presence of mu rhythm at C3 and C4 produces a display that looks like the face of an owl.

The appearance of the mu rhythm over the sensory-motor cortex has been associated with pathology (Gastaut & Bert, 1954; Gastaut et al., 1959), such as psychosomatic symptoms in individuals identified as neurotic. Chatrian and colleagues (1959) demonstrated that suppression of mu activity is associated with one’s movements or when observing someone else moving. In the early 1950s, mu was thought to be quite rare, and various studies identified the prevalence of between 2.9-14% (Schnell & Klass, 1966). In an early version of the textbook Electroencephalography by Niedermayer and Lopes da Silva, the incidence of mu was estimated at approximately 18%. More recent studies using computerized spectral analysis and coherence calculations (Kuhlman, 1978; Schoppenhorst et al., 1980) show the presence of mu in 60% of their study participants.

Mu activity has been correlated with motor cortex functions, as noted above. It appears to be similar to the alpha activity described in posterior areas in response to eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions. Similarly, mu activity seems to be present when the motor cortex is idle and blocked or attenuated when the motor cortex becomes active. Interestingly, mu is blocked with the physical movement of the person being recorded, when that person observes movement, and when the person even visualizes movement. However, unlike alpha, mu activity does not block with eye-opening.

Mu activity has been associated with what has been called the mirror neuron system (MNS), which is a network of locations that are associated with what might be termed learning by observation, mimicry, or imitation. Bernier and colleagues (2007) identify mu as reflecting an underlying execution/observation matching system and studied the relationship of abnormalities in response patterns of the mu rhythm in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). They show decreased attenuation of mu rhythm when adult individuals with ASD observed physical movement in others compared to age- and IQ-matched typical adults. Montirosso and colleagues (2019) show different patterns of mu desynchronization between pre-term and full-term infants at 14 months of age during an action observation/execution task, with full-term infants showing more broadly distributed areas of mu rhythm desynchronization (blocking of mu due to cortical excitation) compared to the pre-term infants.

Okada and colleagues (1992) identified patients with mu rhythm activity that increased with drowsiness, photic stimulation, and hyperventilation as being more likely to experience intractable epilepsy or to suffer from organic brain disorders compared to another group with more well-controlled epilepsy and psychiatric disorders where the mu rhythm showed more typical behavior, i.e., not blocking with eye-opening but blocking appropriately with spontaneous movement or with sensorimotor stimulation.

Finally, Siyang and colleagues (2016) have correlated mu with blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals. They have shown that mu activity's higher power (amplitude) is negatively correlated with the BOLD signal over the sensorimotor network, the attention control network, and the mirror neuron system. This means there is a decrease in blood oxygen utilization when the mu rhythm is higher in amplitude, confirming its nature as a resting state indicator for these systems and networks. Additionally, higher mu amplitude was positively correlated with the BOLD signal in areas of the salience network such as the anterior cingulate and anterior insula. So, it appears that some systems are at rest when mu is active, and some are more active when this is true. This, again, speaks to the complexity of EEG activity and the global, system-wide relationships associated with all EEG frequencies.

Thus, mu rhythm has become an area of increased study and interest, and training mu activity over the sensory-motor cortex has become a fairly common neurofeedback intervention. For example, a psychiatric clinic in Nashville, TN has seen improvement in multiple symptoms when Rolandic mu is trained using z-score neurofeedback (Tim Caldwell, 2020).

The visual identification of mu rhythm activity can be helpful, and task-oriented assessments that show the response to movement or observations of movement should be included in the EEG assessment of potential clients.

There is a similar pattern of activity in the sensory-motor cortex in the 12-15 Hz range that some identify as mu rhythm but which is also labeled as the sensory-motor rhythm (SMR). This is a pattern noted by Sterman (1967) and reported in multiple publications regarding his work with cats (Sterman & Enger, 2006) and subsequently in his work with human participants (Sterman, 1996). Sterman initially trained cats to increase this EEG frequency activity and found that it appeared to prevent seizure activity in the presence of toxic substances. He then taught human participants with intractable epilepsy to produce increased amplitude of SMR with excellent results, and this work was replicated in multiple publications. An excellent review of the history and development of this area of EEG research and training is available in Enger and Sterman (2006).

Neurofeedback training of SMR eventually progressed to working with ADHD clients (Lubar & Shouse, 1976) and others. This pattern is associated with decreased motor excitability and is similar to the sleep spindles seen in stage 2 sleep. Clients learning to increase the voltage of this 12-15 Hz pattern show a marked decrease in hyperactive behaviors. Training in this frequency band is commonly used for clients with ADHD hyperactive or combined subtypes. It is included within the broad, generic beta frequency band. Still, it shows specific characteristics that suggest it doesn’t have the same behavioral or local generation characteristics that more typical beta activity seems to have.

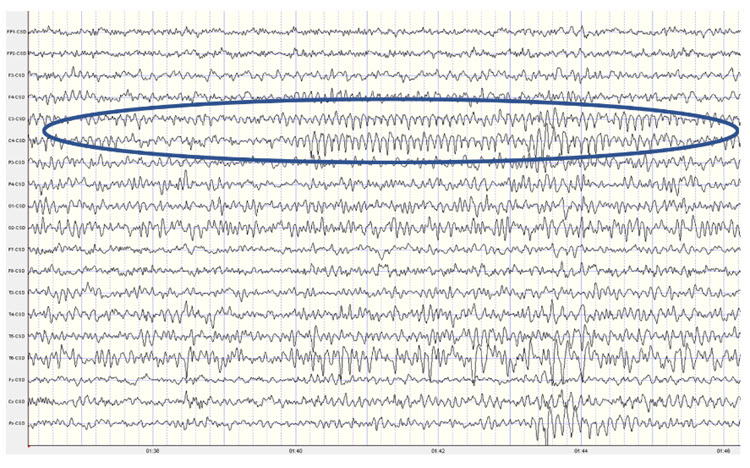

Below is an example of SMR activity in an eyes-open recording.

Note: this is an image of a filtered EEG recording – isolating only the 12-15 Hz frequency band. The montage is longitudinal bipolar, and the scale is 10 uV due to the low voltage of this signal. Observe that activity in this band is present in all electrode locations but does show more of a persistent bursting or spindling pattern in derivations involving central electrodes.

The 12-15 Hz (SMR as defined by Sterman) EEG over the sensory-motor cortex was one of the first EEG patterns to become the focus of neurofeedback training. As noted, many published studies demonstrated the efficacy of training this frequency band in central electrodes for conditions as diverse as seizure disorders and attention deficit disorder. Training this frequency continues to be a commonly used intervention in the neurofeedback field. The controversy regarding whether SMR activity is the same as Rolandic mu or a distinct pattern with unique characteristics is difficult to resolve. When viewing SMR activity in individuals with prominent mu rhythm, the bursting patterns do not appear synchronous, suggesting a separate mechanism of action. Still, these are simply the author's observations and have not been verified by rigorous studies.

The presence of more precisely identified frequency patterns in the EEG with more clearly defined behavioral correlates (e.g., the beta frequency band) is a good reason to be wary of broadly defined EEG frequency bands with a lack of specificity by location or behavior. We will also see this occur in the other frequencies that are covered in this discussion.

The assessment of beta activity includes location specificity and differences between locations, so training choices also target these findings. When training is focused on correcting atypical results, attention must be paid to compensatory behaviors reflected in the EEG. This will be discussed in more detail toward the end of this section.

0.5-3.5 Hz or 1-4 Hz or 0.1-4 Hz – The Delta Frequency Band

Continuing with our somewhat historically-defined EEG frequency discussion, we move on to the delta frequency band of 1-4 Hz or sometimes defined as 0.5-3.5 Hz and even as 0.1-4 Hz. Kane (2017) describes delta as follows:

A frequency band of 0.1–<4 Hz. Greek letter: δ. Comment: for practical purposes, the lower frequency limit is 0.5 Hz, as DC potential differences are not monitored in conventional EEGs (due to the use of AC amplifiers rather than DC-coupled amplifiers for most EEG recordings – author’s note).

This somewhat limited description is partially due to the difficulty of defining cellular activities associated with the EEG from 0.1-4 Hz. Amzica and Lopes da Silva (2017) discuss the delta frequency band in some depth and conclude that the activity in this frequency range represents more than one phenomenon and that frequency-band definitions do not reflect the underlying mechanisms of the various sub-components of this activity.

Amzica and Lopes da Silva state that activities associated with delta frequencies reflect two different EEG phenomena, waves and oscillations. They describe oscillation as a repeated variation of a parameter such as current or voltage between two values with the possible additional characteristic of a regular pattern to that variation. They define a wave as a single variation of a parameter between two extreme values and state that oscillations appear to be made up of waves. Current thinking identifies at least two cellular sources of delta, the thalamus and the cortex.

Thalamic delta oscillations result from two inward currents of thalamocortical cells (Soltesz et al., 1991). These currents appear to be associated with low-frequency membrane potential oscillations in thalamocortical cells that continue even in vitro after removal from the organism. This was identified in studies in rat and cat subjects (Leresche et al., 1991) and verified in human studies during in vivo monitoring (Crunelli et al., 2018). There are intrinsic mechanisms within these cells that result in regular electrical discharges. Crunelli and colleagues show that these oscillations have a rhythm-regulation function as expected and a plasticity function that can shape ongoing oscillations during inattention and NREM sleep, reconfiguring thalamic-cortical networks to facilitate information processing during attentive wakefulness.

Cortical delta oscillations continue even when those neurons are disconnected from thalamic input. Again, this suggests an intrinsic mechanism within cortical neurons that allow these very slow rhythms to occur even without communication from other sources. Grey Walter (1936) identified delta activity in the scalp EEG overlying areas of cerebral tumors. More recently, localized delta activity has been associated with areas of traumatic brain injury (Buchanan et al., 2021). This is one area where quantitative analysis of the EEG can be extremely helpful when evaluating individuals post-stroke or post-mTBI. Areas disconnected from local and/or global networks generally show increased delta rhythm activity and do not function as expected. Neurofeedback training can often help resolve these disconnections or facilitate a reorientation of function to a different set of neurons.

Activity in the delta frequency range appears to represent multiple brain functions. As noted earlier in the discussion of cross-frequency synchronization, delta appears to play a significant role as an underlying pacemaker for organizing and coordinating everything from local activation that results in beta frequencies to global network functions that integrate local information processing results from multiple sensory areas, to interpretive, problem-solving, and decision-making activities, to command-and-control outcomes.

These broadly distributed functions that must be coordinated in both time and space require an underlying physiological mechanism to facilitate such coordination. Crick (1994) suggested the 40 Hz (gamma) rhythm as the binding mechanism, and others have also recommended this. Gunkelman (2005) suggested the glial system as the physiological mechanism and the slow cortical gradient and delta frequencies as the EEG components that reflect the activity of this system, with gamma as an emergent property that only appears when the slow cortical gradient/delta system is bound or synchronized.